Note: This is the first in a series of eight columns written for the Geophysical Society of Houston (GSH) monthly journal on the subject of surviving the downturn. This first appeared in the September, 2016 issue.

Geoscientists without Jobs: A Guide to Surviving the Downturn, Part One

So You've Been Laid Off

As a former boss once explained, you move up when times are good, and hold on when times are bad. For many in the GSH, times are indeed bad. If you’re of or over the median age of SEG and GSH members, this is not your first downturn. If you’re experiencing the cyclical nature of the oil business for the first time in your career, though, it can be traumatic and depressing.

I finished graduate school in 1999, so I missed the major downturn of the mid-1980s. Older colleagues would talk about it in hushed tones, like Obi-Wan Kenobi speaking about the heyday of the Old Republic before the Dark Times—before the Downturn. Like Obi-Wan, though, they spoke in vague generalities, never imparting anything specific or useful about how they survived layoffs, economic hardships, or what led them to ultimately stay in this business to possibly do it all over again.

As of June 2016, more than 350,000 oil and gas workers have been laid off since November 2014 when the battle for market share among oil producers began. Of those layoffs, 118,000 have been in the US, and 99,000 of those have been here in Texas alone. The Houston professional geoscience community has been hit especially hard by the downturn, yet there is scant discussion in the publications of the SEG or GSH about what to do if you’re one of those 99,000. Technical societies are intended to encourage professional development, and these cycles are basic facts of life; therefore, we have an obligation to prepare our members for this reality. That median age demographic I mentioned above? That’s a direct consequence of our failure to prepare geoscientists for the last cycle, and we’re still dealing with the repercussions.

I was laid off in December of 2015. Since then, I’ve had to learn a number of lessons about planning what to do next, developing my skills, maintaining my professional network, looking for jobs (and avoiding scams), building a consulting business to keep the lights on, and managing the stress. What follows is a series of columns on these lessons in the hopes that someone else doesn’t have to learn them all the hard way.

If you’re one of the 99,000, or you think you soon will be, I hope you find something of value here. If you’re an older colleague for whom these lessons resonate with your own past, please take that as a cue to share your insights with your friends struggling in the present.

Part One: So You’ve Been Laid Off

Once I was unemployed, one of my first calls was to a former boss and confidant, Bob Hardage at the Bureau of Economic Geology. He related the story of how he was cut from Phillips in 1986, where he was then Chief Geophysicist. When his manager told him he was out, the paradoxical reasoning was, “You’re our best geophysicist, so we know you’ll be able to find a job quicker than anyone else.” The subtext was clear, though; this was purely a cost-cutting measure. I felt a little better after hearing that.

As weeks went by and I heard about more colleagues being let go, I marveled at the people with years of experience, incredible publication records and amazing technological achievements to their names all being shown the door. After countless conversations which included the phrase, “You mean they let him go?!?”, something which had been repeated to me ad nauseum finally sank in: it’s never personal.

In that moment when your manager comes to your office, says, “Come with me,” and sits you down with someone from Human Resources, the only thing you will be able to think is, “What could I have done differently?” Unless you have a time machine, it’s a pointless question because the answer is always nothing. It was never about you, your skills, your sociability with co-workers, that time you had to re-run a migration that put the project behind schedule, or if you ever picked a bad prospect. Personalizing someone else’s cost-cutting decision is a natural first reaction, but it’s counter-productive. The best advice on offer is to let it go. In this moment, you need clarity for the important work of planning what to do next.

So what do you do next? Do you stay or leave the oil business? Do you look for part-time work or try to be a self-starting consultant? The specifics of anyone’s situation will vary, so here is the basic algorithm I used to constrain my choices with some practical boundaries:

1) Determine a budget to fix a timeline. Take everything out of the budget you reasonably can, figure out your fixed costs, count your available cash and decide how long can you last with a reduced income. It’s important to remember there will be unexpected costs that always come up, like a new set of tires, or that water heater that needs replacing. (Looking back over the last few months, my unexpected costs added 10—15% to my monthly expenses.) Also remember to factor in fixed costs that occur once or twice a year, such as property taxes, auto insurance and vehicle registrations.

2) Estimate how long it will be before you find full-time work doing your previous job. The marketplace for field personnel is different than that for a researcher, and the speed at which each will be hired back is going to be different. There is only so much intelligence one can gather from news sites and trade journals, so it’s important to keep in personal contact with reliable sources of information within the industry. (We’ll talk more about networking in Part Three.)

3) Determine the space between your financial resources and when you think full employment is possible. If there is a shortfall, you have to formulate a plan to cover the gap. Can you work part-time, or do you and your spouse/partner both need to work to make ends meet? How you define “make ends meet” is critical. For example, can you cover 100% of your fixed costs and go indefinitely, or are you only able to cover half? Multiple scenarios are possible; think like a geophysicist and consider the degrees of freedom and underlying assumptions in your financial model.

4) Define an end goal. Facts are facts, but don’t discount your emotions, either. It is important to weigh your satisfaction with your life and career along with the practical choices you face. Are you proud of the work you have done in your career and want to continue in the geosciences? Do you enjoy the challenges and problems you face on a daily basis, or are you disengaged? Maybe you enjoy the technical work but not the circumstances, but you don’t think you have the skills to do something else. (You do, so if you’re thinking about leaving the oil patch, be sure to watch for Part Two.) In any case, you have to define your goal.

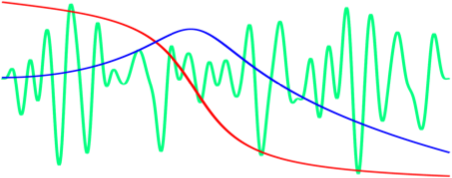

5) Work the plan until the plan doesn’t work. Your circumstances will change. Be willing to adapt, but also recognize that you need to hold your nerve if your plan is to succeed.

Remember, too, losing your job is a trauma that requires grieving. How and when you experience the strains of denial, anger, depression, bargaining and acceptance will be based on your own psychology and circumstances. Douglas Adams penned the best suggestion for these circumstances: “Don’t panic!” Use your analytical skills as scientist to assess your situation, make a plan, and give yourself time to adjust to your new reality. Just in case, though, you might want to hold on to your towel.