Geoscientists without Jobs, Part Two

If you’re one of the growing numbers of recently laid-off geophysicists, the question of career change is obvious. If you’re gainfully employed watching countless colleagues being shown the door, you may also be pondering the same point: should I stay or should I go? Neither Mick Jones nor I can answer that question, but I can offer a way of thinking about the problem.

I’m a geophysicist by training and a pragmatist by nature, and since we spend much of our time working on inverse problems, this seemed a logical framework for analyzing the problem. For those not familiar with the concept, it’s worth taking a brief aside to describe inverse problems as geophysicists see them.

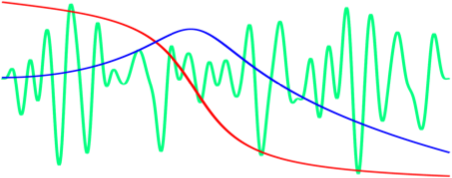

Inverse problems are those in which one attempts to define a model that would predict a set of data. Curve fitting a line to data by tweaking the terms of the equation for the curve is a good example of this. The way we determine how good we fit the model to our data is by minimizing some metric (usually a least-squares error) that measures the misfit between real data and those the model predicts. As we change the terms in our model, the error will get larger and smaller, creating many hills and valleys in our misfit function. These valleys are local minima, and we may cross through a number of them on our search for the overall lowest point, the global minimum.

In geophysical problems with many variables, that misfit function is a surface in a multidimensional space, containing many peaks and valleys. We are forced by mathematics to admit that there are several different models (i.e., several different places on our surface) that can achieve the same fit to our data. That solutions to inverse problems are non-unique is both counter-intuitive and fundamental. Some models may be mathematically possible, but the combination of terms that arises from them might be physically impossible or otherwise unreasonable. This is where experience and guidance from the scientist enters the problem, where we try to constrain our search for solutions to those with some plausible basis.

So, in thinking about the complex interplay of costs, limited income, financial obligations and career objectives, I decided to treat this as an inverse problem.

I define the variable to be minimized as my personal suffering (or that of my family, discounting their suffering for having a geophysicist in their midst). Like all inverse problems, there is no unique solution. I assume there are a number of possible “happy valleys” in the dimensions of this space, and the goals of this exercise are to determine what variables drive the path from one local minima to the next, to measure relative costs, and decide how to decrease overall suffering.

In Part One, I described the steps of a basic plan for the immediate aftermath of a layoff, summarized as:

1) Determine your burn rate for fixed expenses.

2) Estimate the time gap between now and full-time employment.

3) Determine the possible scenarios that will cover the gap.

4) Define an end goal.

5) Work your plan but remain flexible.

This gives you a description of the immediate vicinity of your “suffering landscape”. If you have contingency plans for setbacks such as layoffs, then hopefully you are in a local minimum that will not disappear before you identify the next valley over. If you’re already on the slopes, though, your path to the nearest local minimum might be predetermined for you.

Depending upon your position on the landscape, the Lagrange multipliers might negate the effects of every variable except career change. In other parts of the landscape, other variables might increase your well being just as effectively; for example, maybe you can ride out the downturn as a consultant and have a modest retirement at age 65, but those plans for world travel and a summer home will need rethinking. Perhaps the choice between paying your mortgage and investing in your children’s college fund is a no-win situation that forces career change.

There are two useful insights I gained from treating my choices as a “suffering minimization” inverse problem. The first is that moving between any two local minima will temporarily increase one’s suffering. The nature and extent of that suffering will vary, but at least you will have some sense of what to expect on that journey. The analogy is imperfect, though, because stresses of different types can feed off one another, and once you’re trekking across the landscape, the combination of financial and emotional stresses will make any slope harder to climb.

The second is that the topography of your suffering landscape will vary with time, so take note of the how fast the landscape changes. The safe haven of a local minimum may disappear when financial resources are gone; your hopes of selling your house and moving elsewhere might disappear with a softening real estate market. Steady ground can become quicksand, or a new valley may appear close by. Time can work for or against your depending on your options.

Sticking with a career in geophysics may be an active choice or it may be beyond your control. Of the out-of-work geophysicists to whom I have spoken about this, there are two reasons why they don’t change careers: they don’t need to change, or they don’t think they can. If you’re in the former category, you’re in an enviable position. If you’re in the latter, I have good news.

A well-trained geophysicist possesses a number of highly marketable skills. Computer programming, signal processing, data analysis and mathematical acumen are individually desirable skill sets. If your career has largely been driven by your interest in these skills and their connection to geoscience is only peripheral for you, a career change may be a natural progression. In the exploding world of data science and “Big Data”, there is an ever-increasing demand for people who can combine these skills to analyze large, complicated data sets and derive a set of model parameters to make useful forecasts. Call me crazy, but that sounds like an inverse problem. Geophysicists are arguably more prepared for the coming data-driven revolution than any other discipline, so opportunities abound.

It’s important to realize a career change is rarely a binary yes-or-no decision. You may explore the other valleys in your vicinity for a time, and later decide that your personal Shire is the world of geoscience. Presently, though, that valley is being scoured. No one will fault you for leaving with all those orcs roaming about.